Bessie Dendrinos

TESTING AND TEACHING MEDIATION

Abstract

This paper is the result of a larger

research project on mediation, an innovative aspect of the KPG exams and a communicative activity

launched into the European foreign

language teaching and assessment project

through the Common European Framework

of Languages (2001), is

comprehensively explained in the first

part of this paper, which also discusses

what mediation involves. Given that

teachers, candidates and other

interested parties often confuse

mediation practice with translation, the

nature of the KPG mediation activities

is elucidated, examples are provided,

and mediation tasks are analysed with a

view to ascertaining purpose and

difficulty. What is expected, in terms

of mediation performance, and research

findings regarding the problems

encountered by candidates in the role of

mediators are also presented. Actually,

all the issues contained in this paper

are motivated by the concerns shared by

all those who are apprehensive about

candidates not being prepared for

mediation tasks, which are an important

part of two out of the four KPG test

papers. The reasons are many, but what

teachers themselves say is that they

don’t really know what mediation is and

how to deal with it in the classroom,

that they don’t have the right materials

with which to ‘teach’ mediation. The

wish to familiarize teachers with

mediation as an aspect of language use

worth incorporating into foreign

language programmes is the motivating

force of this paper, which views

mediation and the systematic preparation

for mediation activity as ethical

practice.

Keywords:

mediation, mediator, interlingual and

intralingual mediation, intercultural

mediation, translation, interpretation,

social practice

1. The notion and practice of mediation

Mediation is the act of extracting

meaning from visual or verbal texts in

one language, code, dialect or idiom and

relaying it in another, so as to

facilitate communication. That is,

mediation, which has also been defined

at length elsewhere (Dendrinos

2007a,2007b[1]

and 2006), entails providing information

from a source text that an interested

party has no access to, or explaining a

message contained in a text (verbal or

visual) to someone who does not

understand it.

As users of language(s) and informed

about cultural and social practices, we

are all potentially mediators.

When we assume the role of mediator, it

is so as to participate in a

communicative event, acting as a

go-between, an intermediary whose

job is to help someone understand the

message delivered. We intervene to help

the flow of interaction and facilitate

the exchange. The need usually arises

when two or more parties interacting are

experiencing a communication breakdown

or when there is some type of

communication gap between them. The

mediator intercedes as a meaning

negotiator, undertaking the task of

reconciliation, settlement or

compromise of meanings.

When we perform as mediators, we become

meaning-making agents; that is, we

create meaning for someone else, who is

unable to understand what is going on,

to comprehend a text, whether this is in

a

language

s/he knows well or it is in a

foreign language. We create and

interpret meanings through speech or

writing for our interlocutor(s), with

whom we may or may not share linguistic,

cultural and/or social experiences.

From the above, it becomes obvious that

we mediate when there is need to make

accessible information that a friend, a

colleague, a family member, etc. does

not grasp; it originates from the need

to have

something

clarified, to interpret or reinterpret a

message, to sum up what a text says for

one or more persons, for an audience,

for a group of readers, etc.

Interpreting a word, phrase

or

a whole

text as part of the act of mediation

should not be confused with the job of

the professional interpreter – at least

not if one thinks along KPG lines. The

KPG definition of mediation does not

coincide with the definition provided in

the Common European Framework of

Languages (henceforth CEFR), where

mediation is viewed as synonymous

with

translation

and with

interpretation. There is a rather

sharp distinction between written

mediation in the writing test paper of

the KPG exam (Module 2) and professional

translation of functional, technical or

literary texts. Moreover, there is a

very pronounced distinction between

simultaneous interpretation (at

conferences, business meetings, etc.),

consecutive interpretation (during

speeches, guided

tours)

and other

similar practices on the one hand, and

KPG oral mediation on the other. The

latter concurs with what the CEFR

describes as informal interpretation in

social and transactional situations for

friends, family, clients –

interpretation of signs, menus, notices,

etc. However, mediation is not limited

to interpretation. It may serve a series

of other communicative purposes, such as

reporting, explaining, directing,

elaborating or providing gist, defining,

instructing, and much more.

Usually, when people in real life

mediate – and this is true of KPG

mediation

too – they may resort to

certain translation and interpretation

techniques, but their job is not

to produce a text or speech

equivalent in meaning and similar in

form as when translation and

interpretation are at work. The very

purpose of translation and

interpretation is the production of

configurations which are as close as

possible to the original, i.e. to the

source text. The task of translators and

interpreters is to establish

corresponding meanings between source

and target text, with perfect respect

for the source text – the what

and the how it articulates its

meanings.

Mediators, unlike translators and

interpreters, have the

prerogative

of producing their own text; a text

which may not be equivalent in terms of

form, while it may be loosely connected

in terms of the meanings articulated.

Mediators

bring into the end product their own

‘voice,’ often expressing their take on

an issue. They select which meanings or

messages to extract from a source text

and then decide how to convey them.

Their choice in real life is necessarily

dependent on why the mediator is

interfering, which means that the

outcome of mediation (particularly where

form is concerned) is task specific and

addressor specific. The outcomes of

translation and interpretation on the

other hand are usually text specific,

though the audience for whom the text is

intended is always taken into account.

Put differently, the translator’s and

interpreter’s ‘loyalties’ lie with the

source text, whereas mediators’

loyalties lie first and foremost with

the interlocutor.

Finally, translators and interpreters

have

no ‘right’ to change the discourse,

genre or register of their text; it is

to be the same as the source text. For

example, say that someone undertakes the

job of translating a theatrical play.

What s/he must do is to produce a play

in another language, not a summary or a

review of that play! A mediation task on

the other hand may involve just that. An

advanced level KPG test paper could

include a short one-act play in the

candidates’ L1[2]

and the mediation task could be to have

candidates use L2 to speak on the

meaning of the play (oral mediation

task) or to have them write a review of

that play (written mediation task).

Mediators have the right to

change the discourse, genre or register

of their text, and having the

prerogative to do so is not an issue

because it is an inherent component of

their role as mediators. Imagine that

you are a medical student and you visit

the doctor with your father, who has

been taken ill. Upon leaving the

doctor’s

office, your father asks you to tell him

what the doctor’s diagnosis was because

he didn’t understand a word of what she

said – not because what she said was in

a foreign language, but because she used

medical discourse. So, your father puts

you in the role of mediator, and this

isn’t always easy not only because you

have to think of how to turn medical

discourse into plain language, but

because you also have to interpret the

communication breakdown between doctor

and patient, which may be quite complex.

No matter what, though, your job is to

select those bits of the doctor’s

message that you think are crucial and

say them in a way that the patient (your

father) can understand. If there is

serious illness involved, you may have

to modify or play down what the doctor

said, or you may even consciously decide

to conceal some information so as not to

scare him.

The case discussed above

is

an instance

of intralinguistic

mediation. It does not involve relaying

information from one language to another

but in the same language. In

other words the doctor spoke, say, Greek

and you report the doctor’s diagnosis to

your father also in Greek. Some teachers

would say that this is an act of

transforming direct to reported speech.

But, obviously, this is more than a

(grammatical) transformation exercise,

because what the mediator has to do here

is to select salient information

provided in medical discourse used

perhaps to account for the symptoms and

conveyed in formal register (possibly to

report, instruct, warn, etc.), and to

relay all or part of this to the patient

in simple, everyday, informal language.

Another example

of intralinguistic

real-life mediation is when, say, you

tell your friends Joshua and Laura a

joke in English. While you’re expecting

both of them to laugh, Laura bursts out

in loud laughter but Joshua just smiles

and looks confused. Laura explains

what’s funny about the joke, using

English which is the common language

between the three of you. The act she’s

performing is intralinguistic mediation.

She’s mediating in the same

language, as you did when you went with

your father to the doctor earlier.

Though such tasks are not labelled as

mediation, KPG does use

intralinguistic mediation tasks,

involving only the target language,

i.e., the language tested.

For example, the first activity of the

C1 writing test paper asks the candidate

to extract information from one text in

English and to compose a script using

the information extracted. In many

instances the text to be produced is to

be of a different genre and register

than the source text, as for example

where candidates are asked to read a

webpage which provides information

regarding ‘Education for sustainable

development’ and are asked to write a

review, recommending the webpage to

website visitors (Appendix 1).

Unlike intralinguistic,

interlinguistic mediation

involves two (or more) languages. A real

life example is when you’re watching CNN

and your mother who doesn’t understand

English happens to see a scene which

surprises her. Impressed by it, she asks

you what’s going on. You’ve been

listening to the news and you report to

her in Greek the gist of what’s

happened. It is this type of

interlinguistic (oral) mediation task

that we see in the KPG speaking test,

with

one significant difference: candidates

are asked to mediate only from Greek to

English and never the other way around.

The same is true of written mediation,

whereby candidates are asked to use

information in a written text in Greek

to compose one in English which may be

of a similar or of a totally different

text type, register and style, while the

two texts may have totally different

genre (that is, text type and

communicative purpose). For example, a

writing mediation task could originate

from two Greek ads about houses that a

teacher could easily locate on the

internet. The mediation task that could

be assigned is:

Read the two ads about houses for rent

on the island of Kalymnos, where your

friend Amelia wants to spend one month

in the summer with her family. Write an

email to her to inform her about what’s

available and to recommend one of the

two to her.

We can use the doctor-patient example

provided above to explain further

interlinguistic mediation – the only

kind

of mediation that the KPG actually

labels as mediation. If the cause

of the communication gap between doctor

and patient was language – i.e., that

the interlocutors spoke different

languages (say, the doctor spoke English

only and the patient Greek) – you, as

mediator, would be called upon to relay

salient points of the doctor’s message

in English to the patient in Greek. Or

vice-versa, if the language spoken by

the doctor was Greek and the patient

spoke English only. This latter type of

communicative situation resembles the

context set up for the KPG mediation

tasks in the speaking test. For example,

the November 2005 speaking test paper

contained a magazine page with short

numbered texts about fun activities for

children. One of the related tasks was:

Help your friends who have two children

(aged 10 and 12). They are in Greece for

the summer. Give them advice about

activities that their children would

enjoy. Read texts 2 and 3 and explain

why their children would enjoy these

particular activities.

Obviously, mediation is both a spoken

and written activity in our everyday

life. Therefore, both spoken and written

mediation are tested in KPG, where

candidates produce an oral or a written

text in

L2

for the speaking and the writing test,

respectively, based on one or several

source texts, in L1. The Greek source

texts from which candidates are asked to

extract information are always written

and often complemented with visuals (a

graph, a map, a sketch, a photo).

What has just been

explained

in the

above example concerns the linguistic

mediator. However, increasingly

important is the function of the

cultural mediator[3]

– a role that entails explaining the

social meaning of specific cultural

practices or traditions, filling in

information gaps about social issues,

customs and values, or accounting for

the operation of social institutions,

etc. We conventionally do these things

for listeners or readers who do not

share the same cultural experiences with

us. In other words, we intervene not

because our interlocutor lacks the

linguistic resources but rather the

cultural awareness required; s/he does

not have insight into the cultural

reality in question, or rather what we

call ‘intercultural awareness’ – insight

into one’s own and the foreign culture.

The person in the role of cultural

mediator does have it and is

therefore able to explain things to

someone who lacks it. Think, for

example, of a situation where a group of

Greek friends are talking politics; they

are rather loud, they often interrupt

one another and all talk at the same

time. An English friend, watching, asks

you why these people are fighting. Your

friend’s question puts you in the

position of cultural mediator so that

you explain that they are not actually

fighting; they’re just expressing their

views in a passionate manner.

Actually, the KPG

exams

do assess target

cultural awareness, but indirectly and

not in isolation from language. For

example, in the May 2007 English exam of

B2 level, Activity 7 of the reading test

(Module 1) is an

acrostic quiz. Candidates are asked to

read what people are saying in COLUMN B,

to guess what their job is, and fill in

the gaps in COLUMN A. To fill in item

No. 69 below with the word ACTOR, the

candidate must have quite a bit of

cultural knowledge to pick up the cues

and infer that the person speaking is an

actor.

|

|

COLUMN A |

COLUMN B |

|

69. |

_ _ _ |

O |

_ |

...I auditioned for the part but had no hopes. So, I was stunned and

scared. I’d not done Shakespeare

before and never thought I’d be

the one chosen to do Antony!

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, in order to successfully

complete the mediation tasks of the

speaking and the writing tests of B

level and C level

exams, candidates are

required to have developed not only (socio)linguistic

awareness, but also (inter)cultural

awareness. An example documenting this

is

the B2 level speaking test of the April

2005 exam in English, which contains a

task where candidates are asked to look

at various photos (Appendix 2) and

explain what the purpose of each

ceremony is, and what usually happens on

such occasions. Also, candidates need to

have developed cultural and

intercultural awareness in order to

respond to tasks such as the ones below,

which are from a speaking test activity

of the C1 level exam in English.

Tell us what you think people mean with

the saying “Don’t put all your eggs in

one basket,” and if you think that this

is always true.

There is an English saying which goes:

“Absence makes the heart grow fonder.”

There’s also a Greek saying which is the

exact opposite: “ÌÜôéá

ðïõ

äå

âëÝðïíôáé,

ãñÞãïñá

ëçóìïíéïýíôáé”.

Which one would you agree with and why?

Finally, comprehension tasks in the KPG

exams often include cultural information

aiming at a backwash effect for the

development of intercultural awareness.

For example, the May 2007 B1 level exam

in English contains the activity below.

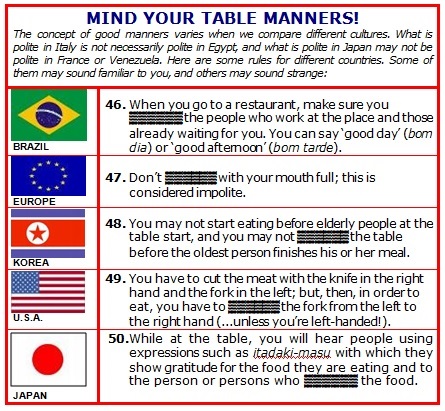

Fill in the gaps in items 46-50 with ONE

word so that each rule makes sense.

2. What KPG mediation involves

What is labelled as mediation in the KPG

exams involves verbal activity intended

to bridge the gap between a source text

in L1 and a target text in L2. The

mediation tasks in the writing tests of

the B1 and B2 level exams require that

the candidate selectively extract

information, ideas and specific

meanings, and then produce a script

which has the same thematic concerns but

often is to be articulated in different

discourse, genre, register and/or style.

The

B1 level Horoscope mediation task

(Appendix 3) is a good example.

In

doing this task, though the thematic

concern of the source and target texts

is similar, successful completion

necessitates production of different

discourse, genre, register and style.

That is, whereas the source text

is a horoscope, the text that the

candidate is asked to produce is an

e-mail.

Also, whereas the source text makes

use of public, impersonal

discourse and semi-formal language, the

target text requires use of more

private, personal discourse and informal

language.

It becomes obvious that mediation is no

easy

job

– neither linguistically nor

cognitively. Mediators have to make

complicated decisions about the

information to be extracted from the

source text, the content of the message

to be delivered and the form of the text

to be created, so that it is appropriate

for the communicative event and useful

for the other participant(s). On the

other hand, mediation tasks usually

demand degrees of literacy in both

languages as well as various types of

competences and skills. In other words,

depending on what the task actually is,

demands may be any one or more of the

following (Table 1):

|

1. |

Sociocultural awareness,

which includes lifeworld

knowledge, knowledge of how two

languages operate at the level

of discourse and genre, as well

as rules of text and sentence

grammar and of the grammar of

visual design. |

|

2. |

Literacies,

i.e. school literacy, social

literacy and practical

literacy. |

|

3. |

Competencies,

i.e. linguistic competence,

sociolinguistic competence,

discourse competence and

strategic competence. |

|

4. |

Cognitive skills

to read between the lines,

select pertinent information,

retain and recall information

for use in a new context,

combine prior knowledge and

experience with new information,

combine information from a

variety of source texts, solve a

problem, a mystery, a query,

predict, guess, foresee, infer,

make a hypothesis, come to a

conclusion. |

|

5. |

Social skills

to recognize the interlocutor’s

communicative needs and be able

to facilitate the process of

communication, negotiate

information by adjusting

effectiveness, efficiency and

relevance to the context of

situation. |

|

Table 1.

What mediation entails

|

As already pointed out, the goal of

mediation is to facilitate interaction

during a communicative event, to fill in

a

communication

gap or resolve some sort of

communication breakdown. The goal

itself sounds uncomplicated, but the

process is rather challenging, as Table

2 below shows.

|

1. |

Developing an understanding of

the problem, the information

gap, etc., by resorting to

one’s socio-cultural knowledge

and experiences. |

|

2. |

Considering the interlocutors’

needs and determining in advance

what type of intervention is

required. |

|

3. |

Listening to or reading the

source text with the purpose of

locating the pieces of

information, or the message

which must be relayed. |

|

4. |

Deciding what to relay from the

L1 text into the L2, decisions

which are not only

content-related but also

language-related.[4] |

|

5. |

Drawing upon the gist of the

source text to frame the new

text and/or recalling bits of

information. |

|

6. |

Planning the organization of the

output. |

|

7. |

Entering a meaning-making

process as the target text is

being articulated. |

|

8. |

Negotiating meaning with the

(real or imagined) interlocutor.

|

|

Table 2. The process of

mediation |

All the steps that the

mediation

process entails are demanding, but step

7 is perhaps the most crucial of all, at

least from a linguistic point of view.

3. The use of L1 and mediation in the

KPG exams

It has been made clear that the writing

and speaking test papers of the KPG

exams in all languages test candidates’

oral and written mediation performance

from the B1 level exam onwards. In the A

level

exams, mediation is not tested, though

there is consistent use of the L1 in the

reading and listening test papers. The

use of L1 at this level functions as a

facilitator to understanding the L2, as

will be shown below.

3.1. The use of L1 in the A level

exam

3.1.1.

Reading comprehension

The texts that candidates have to read

are always in L2, whereas the rubrics

are consistently in both languages, as

in the example in Appendix 4. The

reading comprehension items which

accompany the text (mostly

objective-type items like multiple

choice, multiple matching, True or

False, etc.)

are

commonly in L2, with two exceptions:

There are two activities whose items are

articulated in L1. The function of L1 in

this case is to help candidates

demonstrate their understanding of

content and the semantic/pragmatic

meaning of parts of the text or of

single utterances. The discussion that

follows and the examples provided below

illustrate these points.

Knowing that foreign language readers

understand much more than that which

they are able to produce – partly

because

they lack the ‘vocabulary’ in the target

language to express themselves – L1 is

used to pose rather sophisticated

questions (Appendix 4). The Step 1 task,

originating from a text in English but

with reading comprehension items in

Greek, aims to test the reader’s

understanding of the purpose and gist of

the text. Such items would be too

difficult for the A level reader to

understand if they were posed in English

rather than Greek. The second step aims

to test language awareness, and L1 is

used to pose questions about the

pragmatic meaning of utterances in the

text. Of course, this task also tests

candidates’ ability to establish

semantic equivalence between utterances

in L1 and L2, which is cognitively quite

a demanding job.

3.1.2. Listening comprehension

Texts that KPG candidates

listen to are always in the

target language. The rubrics in Module

3, i.e. the listening comprehension test

paper, are consistently in both the L2

and L1, like in Module 1. The listening

comprehension items which accompany the

text (mostly objective-type, such as

multiple choice or True-False) are in

L2. There is only one activity in the

listening test where L1 is used for a

similar purpose as in the reading

comprehension test: to help candidates

state what they have understood without

having to use L2 at a level of

competence they have not yet developed.

For example, they listen to three

recorded phone messages and they are

asked to respond to True and False items

with regard to the purpose of each phone

message. The choices are in Greek.

4. Testing mediation in the B and C

level exams

The CEFR does not provide a list of

benchmarked illustrative descriptors for

each level of language competence for

mediation, as it does for other areas of

language use. It is our long-term goal

at the RCeL, on the basis

of a

large-scale research project which has

already started, to provide a detailed

account of mediation performance at each

one of the levels where mediation is

tested in the KPG exams. In the

meantime, this paper explains, based on

published KPG specifications and task

description, what the expectations for

mediation task completion in the KPG

exams are

-

in the two test papers that assess

mediation, and

-

at macro levels of proficiency where

mediation is assessed, i.e. at B level

(Autonomous user), which includes

micro-levels B1 and B2, and at C level

(Proficient User).

4.1.

Mediation in the writing test

Mediation tasks in the writing test

originate from text(s) found in printed

or website sources on issues that are

relevant to the average Greek

candidates’ cultural experiences and

literacy.

Tasks are designed to

encourage

the use

of the text as a source of

information rather than as a

meaningful entity in one language to be

rendered as a whole into another

language, as in the case of a

translation task. Tasks in the B1, B2

and C1 level writing test increasingly

require that candidates make reference

to specific points raised in the Greek

text as well as add additional

information which stems from their world

knowledge and experiences regarding the

issue in question.

The assessment criteria for writing

performance at each level, based on an

L1 source text, are the same as the

criteria for

writing

performance for tasks with cues or a

source text in L2. To help the script

rater assess candidates’ mediation

performance, expectations for mediation

task completion are articulated, though

there is a need to standardize these

expectations more for each micro-level,

across languages.

4.1.1.

B1

level writing task completion

expectations

According to the KPG

published

specifications, candidates are expected

to

compose in the target language a script

of about 100 words which:

The Greek texts in

the

B1 level test papers are very often from

popular magazines and touch on topics

such as health and diet, exercise and

daily routines, travel and sports, work

and school, human relations. In other

words, they are on topics that do not

require the use of specialized

vocabulary. Writing mediation tasks stem

from either several brief texts on one

topic, appearing on a single page

usually elaborately designed, or from a

single text in sections, also richly

illustrated. Extended narratives, news

articles or reports are altogether

avoided.

As writing mediation tasks (WMT) from

different

exam administrations show[5],

the script to be produced is

consistently of a genre that candidates

are very familiar with – an e-mail

message – to give advice, warn, inform,

explain, describe, etc.:

WMT 01: The task of the May 2007 exam

administration is based on several brief

texts regarding myths and facts about

nutrition from a Greek magazine.

Candidates are asked to write an e-mail,

giving their friend tips about healthy

eating.

WMT 02: The task of the November 2007 is

based on two horoscopes which are

divided into sections about love and

career, and which also contain a piece

of advice. Candidates are asked to write

an e-mail to a friend, Ursula, to warn

her about spending too much money and to

tell her that, based on what the

horoscope says, her husband might get

the job he’s been waiting for.

WMT 03: The task of the May 2009

administration is based on a single text

about the Mediterranean diet, divided

into sections and complemented with a

visual, which labels the foods in

English to help candidates with

vocabulary. Candidates are asked to

write an e-mail to their friend Scott,

explaining what the Mediterranean diet

is all about.

The cognitive demands in all of

these

tasks are related but different, and the

linguistic requirements vary. In all

three instances, candidates must select

pertinent information from the source

text and use it to convey a message in

L2.

In the case of WMT

01, candidates have

to use the information provided in L1

statement form to give their friend tips

in English about healthy eating. These

tips may be expressed in the form of

suggestions (‘You should … ,’ ‘It’s a

good idea to … ,’ etc.), in the form of

commands (‘Do this … ,’ ‘Avoid that … ,’

etc.) or as factual statements, either

in impersonal or personal forms (‘We

should drink lots of water,’ or ‘People

should not drink …,’ ‘We should not

drink water or soft drinks with our

food,’ or ‘People should not drink … ,’

etc.).

Relevant-to-the-task selection of

information is required in WMT 02. But

whereas in WMT 01 candidates have to

read each short text very carefully and

decide which tip they will use and how

they will express it, in WMT 02 the

required information is in specific

parts of the text, each of which has a

heading. So, candidates skim though and

focus each time on the relevant part,

interpret the message contained in

accordance with what the task asks them

to do, and use the information to a)

warn in the one part of their script,

and b) make a prediction in the other.

In the case of the third example, WMT

03, candidates are required to combine

bits of information from

the

whole text in order to explain what the

Mediterranean diet (described verbally

and visually in the source text) is.

4.1.2. B2 level writing task completion

expectations

According to

published specifications, candidates are

expected to compose a socially

meaningful text in the target language –

a script of 130-150 words which:

-

conveys the main idea of a text in

Greek, or

-

makes a summary of the Greek text, or

-

relays messages contained in the Greek

text

Systematic task description at this

level shows that the L1 texts in the B2

level test papers are on more

sophisticated topics than those at B1

level, such as those from which tasks WMT 04-06 originated.[6]

They are also from a wider variety of

sources, such as promotion leaflets,

newspapers, magazines, books and

websites. Both the source text and the

target text are of a wider variety of

genres. That is, while at B1 level the

source texts are frequently short,

popular magazine texts on everyday

topics and candidates are asked to write

personal messages drawing information

from the source texts, at B2 level there

is a wider range of text types, such as

a graph (November 2003), a tourist guide

(June 2004), a webpage (November 2004),

a newspaper article with a figures table

(April 2005), and a website event

announcement (November 2005). The text

types to be produced are quite diverse

also, as one can see in the examples

provided below.

WMT 04: The task of the May 2006

administration is based on a Greek book

announcement containing factual

information about the novel (title and

author, ISBN, cost, publishing house,

etc.) with the story line of the novel

articulated as a narrative. Candidates

are asked to write a book announcement

for the publisher’s English book

catalogue.[7]

WMT 05: The task of the May 2008

administration is based on four movie

briefs, of the type that one finds in

the film section of a newspaper or

magazine. Candidates are asked to write

a text for the WHAT’S ON guide appearing

in English, recommending two films for

children and two for teenagers.

WMT 06: The task of the May 2009

administration is based on a webpage of

the Greek Ornithological Society,

promoting a volunteer project on the

island of Syros. Candidates are asked to

write an e-mail to their friend Martin,

with whom they have decided to spend

part of their summer vacation doing

volunteer work. Using information from

the website, they are to try and

convince Martin that it’s a good idea

for the two of them to take part in this

project. They are not totally free to

choose any bits of information; rather,

it is suggested that they stress those

aspects of the project which make it

particularly ideal for them, i.e the

location, the flexible dates, the cost,

and the type of work they will be doing.

4.1.3.

C1

level writing task completion

expectations

According to the published

specifications, C1 level candidates are

expected to be able to use their

knowledge and the communicative

competencies they have developed as

users of Greek and the target language,

in order to act as mediators in the

educational, professional or public

sphere. More specifically, candidates

are expected to compose a 200-word

script in the target language in order

to:

-

convey the main idea or supporting

details of a Greek text, or

-

summarize a Greek text, or

-

interpret in the target language the

meaning or meanings of one or more

messages in Greek.

Task analysis reveals that there are

certain differences between the B2 and

C1 level source texts used for

mediation

activity, such as length and

sophistication of text. While a variety

of genres are to be produced, as in B2

level mediation, C1 level production

requires:

-

an impersonal text articulating public

discourse, or

-

a text type which coincides with the

source text, or

-

more specialized vocabulary (motivated

by the source text) and formal register

(instigated by the task).

Actually, at C1 level, the mediation

task obliges

candidates

to stick more closely to the source text

and relay specific pieces of information

rather than select those items they can

write about in the target language.

Below are some examples:

WMT 08: The task of the November 2006

administration is based on the website

of the

SOS Villages Greece, and candidates are

asked to produce a report for an

international organization which funds

important social projects.[8]

The purpose of the report is to promote

the work being done in Greece and to

stress its social usefulness so that

they get the funding they need.

WMT 09: The task here (Nov 2007) is

based on a newspaper article,

translated from English into Greek,

originally published in the Evening

Chronicle. This article, which also

contains two pie charts, presents the

results of a survey on tourist services

in Greece and specifically the

percentage of tourists who believe that

services in Greece are good, mediocre or

bad and the percentages who believe that

it is better, worse or the same as other

EU countries. Candidates are asked to

read the charts and the article and

write a letter to the newspaper editor

to a) express doubt that this is what

people really think of Greece, b) point

out that the article does not reveal how

the survey was conducted and by whom,

and c) present their own evaluation of

tourist services in Greece.

WMT 10: The task of the November 2008

administration is based on the review

(in Greek) of a book which

originally had

been written in Swedish and recently translated into English. Candidates

are asked to use the information from

the book review and write a book

presentation for the catalogue of the

publishing house they supposedly work

for.

The genres to be produced in all the

examples above are obviously more

demanding linguistically than those of

B1 and B2 level: Twice candidates are

asked to produce a report, and a third

time a letter to the editor of a

newspaper. But even when they are asked

to produce a text of a similar type as

that produced at B1 or B2 level, such as

an e-mail, at C1 level the communicative

purpose is quite different (Appendix 6).

4.2. Mediation in the KPG Speaking

Test

Mediation tasks in the

speaking

test

require that information be extracted

from the texts, which are chosen

carefully to suit the average Greek

candidate in terms of age and literacy.

However, there is consideration given to

the fact that there are both younger and

older candidates taking part in the KPG

exams[9];

as a result, texts are chosen and tasks

are developed in a way that some are

more conducive to the adult candidates’

cultural experiences and literacies, and

others to those of younger candidates.

Most importantly, however, the source

texts are selected with a view to being

a rich source of information which

stimulates talk.

For those readers

who

are not familiar

with the KPG examination battery, it

should be mentioned that the speaking

test (Module 4 of the exams in all

languages and levels) involves the use

of a Candidate Booklet and an Examiner

Pack. The Candidate Booklet is an

illustrated publication in full colour,

and each titled page or page section,

which contains texts on a single theme,

is designed up to look like a page out

of a magazine, a brochure, a website,

etc. (Appendices 7a and 7b). For each

text/theme, several tasks are developed

and they are included in the Examiner

Pack, which is not available to the

candidates. The examiner may choose

which task to assign to which candidate

(for the B level test), or to which pair

of candidates (for the C level test).

For the KPG speaking test, two examiners

and two candidates are present in the

exam room. One of

the two examiners assumes the role of

Interlocutor and assigns the tasks to

candidates orally. For the B1 and B2

speaking tests, different tasks are

assigned to each candidate, who is asked

to address either only the

examiner-interlocutor or everyone in the

room. For the C1 level speaking test,

the two candidates in the room are

assigned the same task and are asked to

interact with one another and exchange

information from a Greek source text.

4.2.1. B1 and

B2 level speaking task completion

expectations

According to

the

published specifications, B level

candidates are expected to use the

target language to:

-

relay selected information from L1

texts, or

-

express the gist of L1 texts, or

-

talk about an issue discussed in an L1

text.

Task description indicates that the

source texts are on issues of everyday

concern, such as health and diet, the

environment and saving energy, travel

and holiday, entertainment, home safety,

work and education, public holidays and

celebrations, means of transport.

The B level mediation test requires

one-sided talk, which means that the

source text must provide

enough

information/ideas to allow each

candidate in the room to speak in the

target language for about 2½ -3 minutes,

performing the task assigned.

Analysis of B1 and B2 level

speaking

mediation tasks (SMT) reveals that each

task, which is linked to a single

page/theme/text, commonly points the

candidate to a different part/section of

the text. Each task has a different

communicative purpose, a different

addressee, and it often concerns a

different person, while it may also set

up a different situational context.

Consider, for example, the two out of

the four B1 level tasks for a page

entitled Fruit in children’s diet

from the speaking test of the November

2007 exam in English.

SMT 01: Imagine I am your Belgian

friend and my 14-year-old son never eats

fruit. Read the text and give me some

advice on what I should do to change his

mind.

SMT 02: Imagine I am your Swedish

friend and my children do not like

eating fresh fruit. Read the text and

suggest ways to add fruit to their diet.

It is interesting to note that the

person to be addressed in both tasks is

the examiner in the role of a friend,

and

that the situational context is more

or less the same. However, the language

function to be performed in each case is

somewhat different; that is, in SMT 01

the candidate is to give advice about

what to do, and in SMT 02 to suggest

ways of doing something differently.

Also, each task concerns different

parties and undertakings, which means

that the attention of the candidate is

directed to a different part of the

text; in SMT 01 the candidate is to find

information useful for getting a

teenager to change his mind about eating

fruit, while in SMT 02 the candidate is

to find information useful for a parent

interested in adding fruit to his/her

child’s diet.

Now consider

two more B1 level tasks

from a different page of the Candidate

Booklet, entitled Sea and safety,

from the same oral mediation test as

above.

SMT 03: Your Austrian friend and her

family are going to spend their summer

holidays on a Greek island. Read the

text and tell her what she should be

extra careful about when she takes her

kids to the beach.

SMT 04: You are the leader of an

international camp for young children.

Read the text and give advice to the

young children on how to swim safely.

The person(s) whom the candidates are to

address in both tasks SMT 03 and SMT 04

is not the examiner

or

other people in

the exam room, but a third party they

are to imagine that they are speaking to

– their foreign friend, who is a parent.

The same is true of SMT 04. Again,

candidates are not asked to address the

examiner but a third party, this time, a

group of children. There are, of course,

expectations that the candidates’ talk

will be appropriate for this situational

context, which is different from that in

SMT 03.

Though the B1 level and the B2 level

tasks have much in common, there are

certain differences, which

mainly

have

to do with the topic of the source text

and the type of discourse to be

produced. At B2 level, it is often

semi-formal, impersonal, or requires the

use of some specialized vocabulary. For

example, see below the B2 level

mediation tasks linked to a page

entitled Recycling electrical goods,

from the English exam of the same period

as the B1 tasks above. It is not only

the topic that calls for a more

specialized vocabulary in the source

text, but also each task that originates

from this text. The discourse and

register the candidate is expected to

use when performing SMT 05 is quite

different from that used for SMT 01-04

because the situational context requires

the use of impersonal language, as in

the case of SMT 06, where the candidate

is asked to give advice to a friend not

on a personal matter that has to do with

human behaviour, relations, etc., but on

acting in an environmentally friendly

way.

SMT 05: Imagine you have been asked to

present in English a new recycling

programme for electrical goods. Using

information from Text 1, tell us what

points you will include in your

presentation.

SMT 06: Imagine your German friend

Ingrid wants to get rid of her old

computer. Using information from Text 2,

give her some advice on how to recycle

it.

The situational context is similar in

the B2 level examples below, included

here to explain the differences – even

though

they are subtle – with B1 level

mediation. All four tasks are from the

same test (November 2007 speaking test)

as tasks 05 and 06, and require the

production of some specialized

vocabulary because of the topic. SMT 07

and 08 are associated with the Greek

text on a page entitled Archery,

and SMT 09 and 10 from a source text on

a page entitled A successful job

interview. In addition, the

communicative act to be performed in

each case is somewhat impersonal,

requiring a semi-formal style of talk,

i.e. to tell someone about the benefits

of something (SMT 07), to tell others

what points will be included in a talk

about archery (SMT 08), to give someone

advice on a successful job interview (SMT

09), and to tell others what advice

would be offered to young people looking

for a job (SMT 10).

SMT 07: Imagine your Dutch friend

Marcel wants to take up a new hobby.

Read the text about archery and inform

him about the benefits of the sport and

the necessary equipment.

SMT 08: Imagine you are responsible

for the local sports centre. You’re

going to give a talk in English about

archery, a new sport to be offered at

the centre. Using information from the

text, tell us what points you will

include in your talk.

SMT 09: Imagine your Portuguese friend

Paolo is very anxious because he has got

an important job interview next week.

Read tips 1-4 and give him some advice

on how to be successful at his

interview.

SMT 10:

Imagine you’re going to give a talk in

English to young people who have just

started looking for a job. Read tips 1-4

and tell us what pieces of advice for a

successful job interview you will

include in your talk.

4.2.2.

C1

level speaking task completion

expectations

The main difference between the B level

and the C level oral mediation tasks is

that the latter involve interaction and

not merely one-sided talk. This means

that candidates are required to initiate

and sustain a conversation for about 10

minutes, and during that time to provide

their interlocutor with information and

converse with her/him in order to reach

a decision, resolve a problem, arrive at

a conclusion, etc., all of which demands

negotiation of meanings, ideas and

factual information.

The C1 level

Candidate

Booklet is, in

fact, organized in a way that is

suitable for this interactive mediation

activity: the first half of the Booklet

contains texts for Candidate A, and the

second half texts for Candidate B. Texts

A and B contain different chunks of

information, but they are both on

exactly the same issue and usually from

the same source, as the examples in

Appendices 7a and 7b, with texts giving

rise to tasks SMT 11 and 12. Each

candidate is instructed to look at

her/his own text, on a different page,

but the mediation task they are both

assigned is one such as the following:

SMT 11: Imagine that you and your

partner are planning a trip for the

Christmas and New Year holidays.

Exchange information from your texts and

decide about the most interesting New

Year’s celebration. This decision will

also help you decide which country you

might visit.

Alternatively, with another couple

of

candidates, the task originating from

these texts is:

SMT 12: Exchange information from your

texts with your partner and together

decide on the two most unusual customs

to write about for the special Christmas

issue of your school/local

newspaper/magazine.

This C1 activity, with two

different

speaking mediation tasks, involves

candidates in interaction and

negotiation for which they must have the

competences and skills presented earlier

(Table 1), so they can go through

processes also presented earlier (Table

2). The ultimate goal in each instance,

where candidates must consider different

circumstances, is for them to reach a

common decision.

Similarly, tasks SMT

13

and SMT 14 below

ask candidates to make a common

decision. The texts upon which the tasks

are based are on the issue of Anger

control. Each candidate is

instructed to look at her/his own

page/text and to:

SMT 13: Exchange information from your

texts and together decide on the two

most important things people should

avoid doing when they are angry and on

the two most effective ways to deal with

anger.

Or, alternatively, with another set of

candidates:

SMT 14: Exchange information from your

texts and together decide what pieces of

advice you would give to a newlywed

couple who have just had their first

argument.

Likewise, in other

C1

speaking mediation tasks, candidates are

most commonly called upon to make a

common decision, i.e.:

SMT 15: Read brief book reviews and

exchange information with your partner.

Then together a) decide which two are

the most likely to become best sellers,

or b)which four books you should buy

for your local/ school library.

SMT 16: Read pop magazine article tips

which might help you when shopping, and

with your partner decide a) which two

tips are the easiest to follow, or b)

which two tips are mainly addressed to

women and which to men.

SMT 17: Exchange information from your

texts, and with your partner decide

about a) the two most suitable dogs for

a family with children, or b) the two

most suitable dogs for a woman living on

her own.

5.

Mediation task difficulty

It is clear from the examples and

earlier discussion that both lifeworld

and test mediation tasks are

challenging. In the KPG exams, mediation

entails comprehension in L1 and

production in L2 and, as many studies

have argued,[10]

language and code switching is demanding

in any case, but it is even more so when

it means encoding the message in the

foreign language. Yet, language or code

switching is not the only challenge that

mediation poses.

The preceding sections of this paper

have shown that mediation tasks are also

cognitively demanding. This makes it

essential for activity and task

developers to become increasingly aware

of what is involved in each instance of

mediation, so they can control the

cognitive load and linguistic demands of

each activity,[11]

according to the level of language

proficiency that is tested, as well as

according to the age and literacy of the

candidates to whom the exams are

addressed.

The statement about consideration of the

above variables (level, age and

literacy) having been

made,

I must also add that the three are not

necessarily dependent upon one another.

There is no direct correlation, for

example, between proficiency level and

cognitive load, which means that there

may be a more cognitively demanding

mediation task for lower proficiency

level candidates and vice-versa.

However, cognitive load is contingent

upon age and literacy, and this may be

linked to higher level testing.

There are

also

strong indications in the

preceding sections that the demands and

the linguistic requirements of each

instance of mediation are both task

specific and source text specific.

This is why when a mediation activity at

each level of KPG testing were presented

earlier, the type of texts used as

sources of information and the types of

tasks set were discussed on the basis of

test level. However, these are important

considerations which need to be

explicitly stated and further clarified

– perhaps with examples.

Let us begin with an example about

task specific difficulty and ask

you, the reader, to consider two

different

tasks

on the same topic, which

is also a variable that has to do with

activity complexity. The activity topic

is Illegal immigration, and the

two tasks with varying degree of

difficulty are the

following:

A. Task 01 asks candidates to

gather information about the issue from

a variety of source texts and to present

the pros and cons of the social

inclusion of immigrants.

B.

Task 02 asks candidates to

read an editorial about illegal

immigration and say what they think the

author’s opinion about the social

integration of immigrants is.

Undoubtedly, the cognitive load of Task

01 is greater than that of Task 02. Both

the cognitive load and the linguistic

demands, on the other hand, are very

much dependent on the source texts – how

many there are for Task 1, what

discourse they articulate (e.g. media or

social science discourse), and how the

source texts of Task 1 in particular are

organized.

To illustrate further how mediation

requirements are strongly related to the

source text – i.e. they are

source

text specific – we should turn

attention back to one of the mediation

tasks discussed earlier, WMT 01. The

language of the text on which this task

is based is too difficult for B1 level

candidates to translate. Therefore, if

they want to be able to respond to the

task at hand, they need to understand

the information conveyed in L1,

interpret it in relation to what is

asked of them, and use their

interpretation to give tips about a

healthy diet to their friend in an

e-mail message. Below are two of the

Greek texts and sample responses to the

task from candidates:

Ïé ðïíïêÝöáëïé ó÷åôßæïíôáé ìå ôçí

áöõäÜôùóç ôïõ ïñãáíéóìïý

ÁëÞèåéá. Ç

áöõäÜôùóç (dehydration)

åðçñåÜæåé áñíçôéêÜ ôéò ðíåõìáôéêÝò

ìáò ëåéôïõñãßåò. Óõìðôþìáôá Þðéáò

áöõäÜôùóçò åßíáé, åêôüò áðü ôïí

ðïíïêÝöáëï, ç æÜëç, ç êüðùóç êáé ç

äõóêïëßá óõãêÝíôñùóçò. Áîßæåé íá

óçìåéùèåß üôé ï åãêÝöáëïò

áðïôåëåßôáé êáôÜ 80-85% áðü íåñü.

Translation into English

True: Dehydration

affects our cognitive operations

negatively. The symptoms of

dehydration are – besides headaches

– dizziness, fatigue and inability

to concentrate. It is worth noting

that 80-85 % of our brain is made of

water.

Candidates’ responses

1.

You must drink a lot of water. It’s good for you and you

don’t get headaches

2. Drink a lot of water every day not to have headaches and

feel tired.

3.

Did you know that our head is 80-85% water? Drink lots of

water. You should not get dehydrated.

ÐñÝðåé íá ðßíïõìå õãñÜ ìå ôï öáãçôü

Ìýèïò: Ç êáôáíÜëùóç õãñþí ìå ôï öáãçôü

ðñïêáëåß áñáßùóç ôùí õãñþí ôïõ

óôïìÜ÷ïõ, þóôå íá êáèõóôåñåß ç ðÝøç

ôçò ôñïöÞò êáé íá ìç ãßíåôáé åðáñêÞò

áðïññüöçóç ôùí èñåðôéêþí ïõóéþí ôçò.

Êáëü åßíáé íá ôá áðïöåýãïõìå êáé ãéá

45 ëåðôÜ ìåôÜ ôï öáãçôü.

Translation into English

Mistaken:

Consumption of liquids when we eat

causes tapering of stomach liquids

so that digestion is delayed and the

nutritious substances of our food

are not absorbed. We should avoid

drinking liquids for 45 minutes

after our meal.

Candidates’ responses

1. You shouldn’t believe all that you hear. Some people say

that it’s bad to drink water and stuff

with our food. That’s not true.

2.

It’s a lie that we should not drink liquids during and for

a long time after we eat.

3.

You should drink water or other things with your food. It

helps you to digest better.

What

we

can see in the

above

responses is that candidates were able

to function as competent mediators and,

by using specific communication

strategies, they were perfectly able to

deal with the task at hand. In fact,

this seems to be the case with mediation

performance in the exams of all levels

in English. Descriptive statistical

analysis we have been carrying out at

the RCeL shows that, despite EFL

teachers’ worries about mediation tasks

being ‘too difficult,’ there is no

statistically significant deviation in

the scores that KPG candidates’ are

assigned for the two activities. What is

even more interesting as we look at the

results of our analysis is that

sometimes candidates’ scores in the

mediation task (Activity 2) is higher

than in the writing task (Activity 1).

6.

Mediation

performance

Mediation

has a crucial role in today’s world of

multicultural contexts that increasingly

demand cultural and linguistic

negotiation for successful participation

in the communication process, ‘producing

oral or written texts in which forms and

words are manipulated to extend further

understanding across cultures’ (Valero-Garcés

2009). This is the main reason that I

have decided to concentrate on this

important topic. In addition, I also

feel the need to give the mediation

component of the KPG exams the attention

it deserves. Therefore, I am publishing

on the subject (Dendrinos and

Stathopoulou, 2010, Dendrinos 2006),

working with postgraduate students (Stathopoulou

2008),[12]

(Stathopoulou 2009, Voidakos 2007),[13]

and with PhDs researching oral and

written mediation (Stathopoulou, 2013a).

Furthermore, I am directing a number of

large-scale projects under way at the

RCeL, which progressively provide a more

accurate account of mediation

performance and performance

expectations. The work carried out in

this fascinating area permits us to talk

about mediation in an informed way and

to identify the problem areas to be

dealt with when teaching or coaching for

mediation practices.

6.1 Written mediation performance

The major data bank we have developed at

the RCeL, with its corpus of thousands

of KPG candidate scripts classified

according to the mark they have received

by trained script raters, has opened the

possibility to conduct systematic

research on the written mediation

performance of candidates.

Stathopoulou

(2013a), having recently

completed her PhD thesis on the topic

gives us insights into what mediation

entails and what types of written

mediation strategies lead to the

achievement of a given communicative

purpose. Drawing data from the KPG Task

Repository and the KPG English Corpus,

she examined KPG test tasks and

candidates’ scripts in order to create a

levelled mediation task typology and an

Inventory of Written Mediation

Strategies, which may provide the basis

for the creation of mediation-specific

levelled descriptors (see also

Stathopoulou 2013b). These will in turn

make reliable assessment of the

mediation performance.

One

of

the MA studies

(Voidakos 2007),

which set out to

describe B2 and C1 level mediation

performance by means of analyzing 283

scripts produced by KPG candidates, has

provided insights which suggest that

candidates’ have the following common

problems[14]

in written mediation performance:

-

They tend to include as much information

as possible from the source text, rather

than selecting only

relevant-to-the-context pieces of

information. This test-taking strategy

does not favour candidates, not only

because they are penalized when their

scripts are longer than they are

supposed to be, but also because they

are more likely to end up with more

instances of inaccurate or inappropriate

English language use.

-

They pay close attention to producing in

L2 structures and forms which correspond

to L1, as they believe that this is what

is expected of them.

-

They tend to pay little attention to the

discourse, genre, register and style of

the text to be produced, which may be of

a different text type than the source

text. Instead, they tend to produce the

same text type and this results in

inappropriate language use, since the

language features of a text are dictated

by its genre.

In the aforementioned

study, Voidakos

finds that there are indications that C1

level candidates perform slightly better

in mediation tasks than B2 candidates.

To qualify this claim, I should say that

what she means is that C1 candidates

seem to make more frequent and effective

use of the necessary mediation

test-taking strategies.

This claim

raised

a noteworthy question, for which there

was no conclusive evidence in the study:

Are more proficient L2 users better

mediators? My guess at that point was

that this is true only when there are

other factors at play too, such as age

(and therefore the cognitive capacity

which develops with age), literacy level

in both the source and the target

language, and task-specific skills.

This

assumption

was an issue of concern

in a later study, along with another

hypothesis, born out of our ongoing

examination of candidates’ mediation

scripts. The hypothesis was that

mediation performance is contingent not

only on candidate, but also on task

variables. In other words, mediation

performance may be ‘better’ or ‘worse’

depending on who is doing it

(her/his age, literacy, knowledge,

skills, etc. in both languages) but also

depending what s/he has to do.

Aspects of

what

I had come to suspect

have now been investigated by Stathopoulou (2009).[15]

Her study, exclusively on B2 level

written mediation performance, was

carried out with a view to supporting

the claim that when mediating, the

source text necessarily regulates the

target text, and the visible traces may

vary from weak to strong, depending on a

series of factors. A total of 240 B2

level scripts were analyzed for the

purposes of the study, which ultimately

offers interesting results and

conclusions about KPG mediation

performance.

As in the

case

of the previous study,

the scripts analyzed for this

dissertation had also been randomly

selected from the RCeL script corpus:

half of the selected scripts were from

the ‘fully satisfactory’ category, and

the other half from the ‘moderately

satisfactory.’ The two categories of

scripts were compared, showing that

fully satisfactory scripts were less

regulated by the source text than the

moderately satisfactory, and that the

hybrid formations in fully satisfactory

scripts are perfectly ‘acceptable’ in

English; that is, as Stathopoulou puts

it, they contain ‘fairly successful code

meshing structures that create no

problem of intelligibility to the

reader.’ Other interesting findings in

her study are the following:

-

Hybrid formations on the borderline of

being acceptable in English, in both

fully or moderately satisfactory

scripts, constitute violations on the

level of pragmatics rather than the

level of semantics or formal grammar.

-

The scripts

contain a number of strongly

regulated constructions which are

unsuccessful in relaying the message(s)

of the source text.

-

In moderately satisfactory scripts,

one notes a tendency towards

word-for-word translation of

complete sentences, whereas in fully

satisfactory scripts, this tendency

is on the lexical rather than the

sentence level. Moreover, moderately

satisfactory

scripts

more frequently than fully

satisfactory scripts transfer

language elements from one language

to the other without adjusting them

so that they are appropriate for the

linguistic and social context. Thus,

they violate English word order

restrictions, make inappropriate use

of prepositions and other words, as

well as language structures, such as

modality.

-

Fully satisfactory scripts are not

as strongly regulated since the

source text information is

paraphrased, and when they do

contain hybrid formations, these are

considered

acceptable

in English; that is, successful code

meshing language items.

-

Finally, in moderately satisfactory

scripts, information seems to have been

selected on the basis of what

information was easily transferable from

one language to the other, rather than

on the basis of what information was

relevant to the communicative demands of

the task. Stathopoulou observes that

‘any ideas that candidates were unable

to relay, probably due to limited

linguistic resources, were omitted.’

6.2 Speaking mediation performance

Greek privacy protection laws do not

allow us to record the KPG speaking test

on DVD; therefore, we have no access to

digital information, on the basis of

which we can study oral mediation

performance.

However, we do have valuable information

from the feedback forms that our

examiners complete after every exam

administration, while we also have the

detailed accounts of candidates’

performance from trained observers,

whose job is to assess the speaking test

tasks, the procedure, and the examiners.

Analysis of this data is under way, and

it will soon be published. Presently, I

include below some of the remarks that

have been recorded:

-

Younger and linguistically less

competent C1 candidates make serious

attempts to translate the source

text rather than to

relay

selected information.

-

B1 and B2 level candidates who are

obviously

unprepared to take on the role of

mediator seem to feel awkward and

less confident about what it is they

are to do.

-

There are instances when B1 and B2

level candidates refrain from making

any use of information in the source

text.

They

simply speak on the theme of the L1

text. When their oral English is

good, examiners are divided as to

what to do since they have been

given no thorough instructions on

how to deal with this matter.

-

In C1 level oral mediation, when

candidates

are required to interact and

exchange information from their

source texts in order to reach a

common decision, they sometimes do

so by using only a few points from

the text, and then draw from their

own experiences.

-

Both candidates and teachers preparing

them need to familiarize themselves

further with the nature of

mediation

activities. KPG examiners also need more

training on this new aspect of

assessment.

7.

Training

for mediation

If it is indeed

true

that mediation

tasks are very difficult, the first

question that comes to mind is whether

it is fair – i.e. if it is ethical

– to test it. In asking this question,

it is only right to reveal that

the

inclusion of mediation in the test

papers of the KPG exams has not been

without reaction in the Greek language

teaching scene – though, admittedly,

those that have been positioned most

strongly against it are L1 English

speakers who have found jobs teaching

English in Greece. These people, many of

whom have not been trained to teach a

foreign language or to teach at all, and

who are nevertheless highly regarded

simply because they are native speakers

(NSs) of the language they are teaching,

benefit from the exclusion of the

learners’ mother tongue from the

classroom, from the teaching materials,

and so on.[16]

There are also a number of Greek EFL

teachers who react as strongly, unaware

of what this reaction of theirs

conceals. However, the largest

percentage of Greek EFL teachers are not

negative; they are sceptical because

candidates are not really prepared to

perform as mediators since it is not

part of the mainstream TEFL materials or

practices. And, of course, it is only

natural that teachers worry about an

element in a suite of national exams

that is not legitimated by the

established international exams trade.

If it were, it might more easily have

been considered a valid test element and

its inclusion would immediately seem

more logical and justified. As things

now stand, the legitimisation of

mediation in the exams is through its

endorsement via the CEFR.

The

reason

that mediation and, in

general, the use of L1 is absent from TEFL textbooks and other materials

produced by the international or

multinational publishing industry is

profit. If it were to localise textbooks

and other materials, companies would not

make as big a profit as they do now when

they make one product for international

use. And, if something is not in the

textbook, it is not legitimate

curricular knowledge – especially for

those who ‘teach to the book’ –which is

true of the largest percent of foreign

language teachers in Greece and

elsewhere (cf. Dendrinos 1992). Hence,

the omission of mediation practice from

foreign language textbooks is a basic

factor for its prohibition from the

foreign language programme. All this

means, of course, that foreign language

learners are not systematically

trained for their role as mediators,

though they frequently practice

mediation in their daily lives.

This

reality

provokes us to amend the

question above: Is it fair not to help

foreign users learn to communicate in a

way that is valuable in their daily

lives, just because the dominant foreign

language paradigm triggered by economic

and symbolic profit does not promote it?

The answer is No. It is not fair

or ethical to refrain from training

learners to exploit language in ways

which will be of practical use to them.

But, how

does one do that? Greek EFL

teachers, who are increasingly turning

attention to mediation, tell us that

they don’t know what materials to use in

order to ‘teach’ mediation – a problem

which is easily solved since nowadays

there are all sorts

of authentic materials suitable for

classroom mediation practice available

on the internet. The more complicated

question has to do with ways of teaching

mediation. The most common EFL teacher

question is: ‘What is it exactly that we

should teach?’ ‘Do we teach,’ they

wonder, ‘aiming at the development of

all the knowledge and skills mediation

seems to require?’

The

response

to this question is that this would not